Radio and Cinema

-

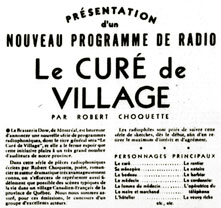

La Patrie, 14 January 1935, p.13

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

-

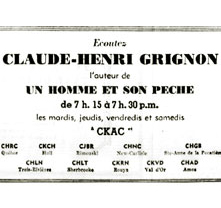

Le Petit Journal, 20 May 1945, p.35

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

-

Hector Charland and Estelle Maufette preparing a new episode of the radio serial Un homme et son péché

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 2001.0658.PH.0425

-

Claude-Henri Grignon (centre) signing a contract, with Paul L’Anglais to his right and René Germain to his left.

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 2001.0655.PH.0452

-

Le Petit Journal, 27 August 1950, p.42

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

-

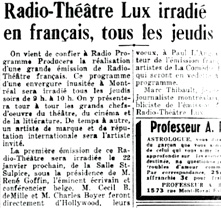

Le Petit Journal, 11 January 1942, p.44

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Radio carried out various functions in Quebec society of the 1930s, 40s and 50s. In the first place, it served to promote the French language across the province. It also facilitated the development of a home-grown star system, which film and television would soon make use of. It also tended to unite and homogenise French Canadians, bringing the culture and entertainment of the city to rural dwellers and giving voice to representatives of the province’s regions. Quebecers from one end of the province to the other came to share a number of references and concerns: from Montreal to the Gaspé, people worried about the lot of poor Donalda, persecuted by the miserly Séraphin in Un homme et son péché, a popular radio serial whose broadcasts on Radio-Canada began in 1939.

Radio Makes Inroads

In Canada, it was not until 1929 that radio stations began to obtain permits to broadcast on a precise frequency. From 1931 to 1941, the percentage of French-Canadian households with a radio receiver increased from 37.5% to 70.6%, reaching 88% a decade later. By the early 1940s, 16 radio stations had been established in Quebec, 14 of which broadcast in French, thereby providing Quebec talent with a large market for their work.

From Radio Serials to Films

In 1935, the writer Robert Choquette created the province’s first radio serial, Le curé du village, for the radio station CKAC. The great success of this series launched this typical Quebec cultural product, whose influence can be seen still today in television serials on the province’s television networks. Soon after it began broadcasting in 1936, Radio-Canada joined in with series such as La pension Velder (Robert Choquette, 1938), Vie de famille (Henry Deyglun, 1938) and Un homme et son péché (Claude-Henri Grignon, 1939). Radio serials enjoyed their heyday in the 1940s, before the arrival of television.

Radio serials were one of the principal sources of inspiration for Quebec films in the latter half of the 1940s. In addition to recycling some of the stories initially developed for radio (Un homme et son péché, Le curé du village), Quebec cinema was impregnated with the radio serial’s aesthetic and archetypes.

A French-Canadian Star System

Radio also contributed to the rise of a true French-Canadian star system. People throughout the province recognised Hector Charland, who played Séraphin on the radio and in the two films adapted from Grignon’s novel, Un homme et son péché and Séraphin. Ovila Légaré became known through Le curé du village, in which he played the title role on both the radio and the big screen. Jeanne Demons was also very successful in pieces by Henry Deyglun on the radio before starring in the film Coeur de Maman, also written by Deyglun. Gratien Gélinas also started out in radio, at the station CKAC in 1937, before moving to theatre and cinema.

The best representative of “visual radio”, however, was Henri Letondal. An actor, singer and scriptwriter for the radio station CKAC, he contributed to the creation of dozens of radio plays, some of which, such as Meurtre au studio and La photo révélatrice, made use of various formulae developed by popular cinema. Letondal soon became a star of theatre and film.

In 1947, Guy Mauffette and Jacques Normand launched La parade de la chansonnette (CKVL), giving new life to French song in Quebec. The following year Normand hosted the same singings stars on the cabaret “Le faisan doré”. All these experiences led to the film Les lumières de ma ville, which starred a number of personalities well-known for their work in radio, including Guy Mauffette, Monique Leyrac, Paul Berval and Albert Duquesne.

The French-Canadian star system was reinforced by magazines dedicated to the world of radio. A popular newspaper such as RadioMonde promoted Quebec movie stars as much as the radio programs where they began their careers. Some newspapers, such as La Patrie, Le Petit Journal and Photo Journal, also had columns on radio.

The Quebec public’s infatuation with radio stars also prompted movie-theatre owners to work with radio stations. Residents of Montreal could thus regularly listen to live radio broadcasts from the Théâtre St-Denis or the Odeon cinemas.

Finally, we should note that in order to support this nascent star system the singer René Bertrand organised the Fédération des artistes de la radio in 1937. This trade union became the Union des artistes lyriques et dramatiques in 1942 and, in 1952, simply the Union des artistes.

Duplessis and Radio

Following Canada’s declaration of war in September 1939, the federal government subjected the country’s radio stations to censorship. Like the National Film Board, founded that same year, this initiative was poorly received by the Quebec premier of the day, Maurice Duplessis, who saw in it another example of the federal government’s interference in the province’s affairs. The Canadian Institute on Public Affairs, created by the federal government in 1954, also irritated Duplessis: the CIPA’s Annual Conference, broadcast on Radio-Canada, often contested Duplessis’ conservatism. Duplessis also took a dislike to certain private radio stations which took the side of the workers in labour disputes. To counterbalance the influence of the federal government and the private broadcasters, in 1945 the Duplessis government adopted a law for the creation of a provincial radio service, the Office de la radio du Québec.