Religious Cinema

-

Photographic portrait of Jean-Philippe Cyr.

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 2000.0206.PH.01

-

Albert Tessier at work.

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 2000.0050.PH.01

-

Maurice Proulx filming a farmer for his film Les ennemis de la pomme de terre (1949).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise 2006.0344.PH

-

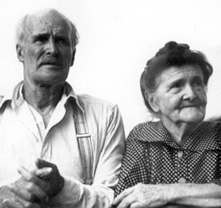

A pair of rural residents in the film Hommage à notre paysannerie (Albert Tessier, 1938).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.6023.PH.01

Filmmaker Clerics and Nuns

Why did priests and nuns begin making documentaries and even poetical films in the 1930s, knowing that Catholic Church officials continued to be distrustful of cinema? They understood that a simple film was worth many sermons, and could in addition reach many more people. Their initiatives were soon encouraged by their superiors, who were happy to use the medium to preserve their hold on the collective imagination.

Passionate Amateurs

These amateur filmmakers, who never worked with professionals, were guided by their love of the image. Their films were personal initiatives, or on a few rare occasions the product of a commission, the result of their desire to use the most modern and effective forms of propaganda. To learn how to make films, most filmmaker priests and nuns had nothing more than a camera instruction manual or a friend’s advice. They adopted various styles, especially the documentary, and specialised in a few fields of interest to a broad sector of the public such as education, nature and religion. Many of them liked to end their film with a pretty sunset.

Historians and Anthropologists Unaware of Each Other’s Existence

The films made by these passionate amateurs have great heritage value. They are often the only documents on film we have of many events of their day and of working methods, clothing styles, certain celebrations, daily life, etc. Above all, they shed light on some of what went on inside convents and religious orders. This, for example, is the case with Jean-Marie Poitevin’s À la croisée des chemins.

One of the very first of these filmmakers, Albert Tessier, became an illustrator of the beauties of nature, a defender of rural values and an advocate of “modern” education for girls. In the same spirit, Thomas-Louis-Imbeault (1899-1984), a college professor and later a priest, set out to reveal the beauty of the Charlevoix region, the Saguenay and the Île aux Coudres. In Chicoutimi, Léonidas Larouche (1907-1991) also filmed numerous images of the region and the rest of the province. He even had a sound studio.

Maurice Proulx, because he was a professional agronomist, had quite concrete educational objectives without at the same time failing to proselytise for Christian values. Essentially pedagogical objectives were also behind the work of the biologist and professor J-Albert Caron (Father Venance, a Capuchin friar, 1895-1966), who made a number of documentaries on natural science. Brother Adrien-Rivard (1890-1969) of the Sainte-Croix Congregation, a botanist, the founder of the Cercle des jeunes naturalistes and a disciple of Brother Marie-Victorin, embellished his gatherings and lectures with numerous films on Quebec’s flora.

Even Nuns Were Joining In

In the 1930s nuns from various religious communities, no longer content simply to consume pious films, decided to make their own. As the feminist historian Jocelyne Denault relates, their work took three forms: “recruitment films”, whose goal was to give viewers a sense of religious calling and ensure a supply of new nuns in their institutions; “souvenir films” which, like most amateur films, were a kind of family album or recording of significant events intended to recount the history of their order; and “prayer films”, which were not without a poetic quality and in which images of nature and pious objects were accompanied by religious texts. Some of these “filmmakers” learned the basics of their art from lessons given by Herménégilde Lavoie.

Like the missionaries of earlier times, such as the Jesuits using their Jesuit Relations to correspond with their superiors and benefactors and communicate to them everything they observed about the “savages” of New France, priests such as Louis-Roger Lafleur and Maurice Proulx began making documentaries in the 1930s about native peoples in various parts of the province. These documentaries have undeniable value, especially as they were part of an effort to rehabilitate the image of First Nations peoples.

Widely Seen Films

These films were never shown in commercial movie theatres. Who saw them, then? They were seen by hundreds of thousands of young people in schools, parish halls, convents and boarding schools. Viewers also often had the chance to meet the filmmakers, who came to lecture alongside their films.