Film and French language

-

La Patrie, 30 July 1931, p.7

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

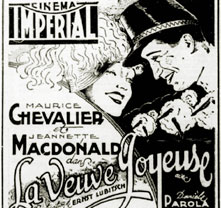

La Patrie, 31 May 1930, p.21

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

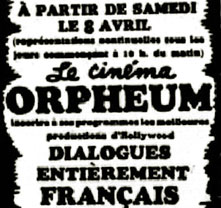

La Patrie, 1 April 1944, p.38

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

Le Petit Journal, 22 September 1935, p.15

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

French on Movie Screens

Before the arrival of the talkies, Hollywood imposed its language on practically every movie screen in Quebec. French intertitles were rare.

Montreal’s Palace theatre was the first movie theatre in the country to convert to sound cinema in the late 1920s. On 1 September 1928 it screened Street Angel by Frank Borzage, a film with a few talking scenes (in English) along with musical accompaniment and synchronised sound effects. The newsreels screened alongside it contained speeches by political figures, including the president of France speaking in Carcassonne. These were the first words in French heard in a Canadian movie theatre since the brief experiments with talking views at the Ouimetoscope and the Nationoscope in 1907.

French on the Loudspeakers

Hollywood quickly realised that the talkies would transform film aesthetics and that they could no longer distribute their films in English alone. Beginning in 1929, they set to work.

On 17 January 1930, the Palace announced that it was “once again the first on the continent, this time to screen the French version of a talkie shot in North America”. The film was the French version of Ernst Lubitsch’s Love Parade, which was shot in Hollywood and featured Maurice Chevalier singing and speaking some dialogue in French. The film also had subtitles in French superimposed on the image, a new technique.

At the same time, a few Hollywood studios began to shoot “alternative versions” of films in French at the same time as the original version in English. These versions, shot on the same set as the original version, featured a partial French-speaking cast; the rest were American actors reciting their lines in phonetic French. Fifi D’Orsay and Pauline Garon, for example, played in Lubitsch’s La veuve joyeuse. In the original version, The Merry Widow, their roles were played by American actresses.

The Palace was once again the first in Montreal to show one of these alternative French versions. On 30 May 1930, the day’s final screening of Hobart Henley’s The Big Pond, another musical comedy featuring Maurice Chevalier, was followed at 11:00 p.m. by a screening of the alternative French version of the film, La grande mare. These late-night screenings had to stop two days later, however, because of a municipal regulation. Nevertheless, La grande mare returned to the Théâtre Français on 9 August and then played at the Saint-Denis from 23 August.

In 1931, Hollywood enlisted Laurel and Hardy for another comedy shot entirely in phonetic French, Les carottiers, an omnibus of Be Big! and Laughing Gravy which Jos Cardinal screened in September at the Saint-Denis.

Paramount Makes Films in France

In addition to producing alternative French versions in Hollywood, Paramount acquired studios in Joinville, a suburb of Paris. There it produced films by filmmakers from a variety of countries based on scripts which were supposedly adapted to the culture of their country of origin. Spanish filmmakers, for example, made films in their own language, as did Italian and German filmmakers. Naturally, French-language production was even more important, because the French-language market was very lucrative and extended to Belgium, Switzerland, Quebec and parts of Africa.

Dozens of French-language films were thus produced in France by Paramount, which employed hundreds of the country’s biggest stars and best directors. As soon as they were finished, these films were shown in Quebec, distributed either by Regal, a Paramount subsidiary, or by France-Film.

The French Language Remains Marginal in Movie Theatres

Nearly two years passed after the arrival of the talkies before a Montreal movie theatre dedicated itself to films made in France, although the truth is that France was late converting to sound. This theatre was the Saint-Denis, which Jos Cardinal rented from its owners in Toronto. Initially, he put on live entertainment in French and American films in their original version. On 31 May 1930, he converted the Saint-Denis to French cinema and screened the first talkie made in France, André Hugon’s Les trois masques. Cardinal subsequently obtained films from France-Film. It was because of the Saint-Denis in particular that the famous slogan “Le succès est au cinéma parlant français” ame to pass.

Throughout the 1930s, English dominated most Quebec movie theatres. This can be accounted for in part by the fact that movie theatre managers preferred to do business with American distributors, who could provide them with a steady supply of films. Above all, however, it was a result of the public’s infatuation with the different genres—musical comedies, westerns, crime films, lavish historical films, etc.—that Hollywood produced and which guaranteed its success, in Quebec and elsewhere in the world. Even though some viewers didn’t understand these films’ dialogue, their stories were simple enough and their action spectacular enough to captivate them.

Dubbed Films as the Path to Success

Experiments in dubbing American films were carried out on only a few occasions in the 1930s. Pur sang, a French version of the film Sporting Blood by Charles Brabin, a 1931 film starring Clark Gable, opened on 5 August 1933 at the Saint-Denis. The following year, Le signe de la croix (Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross) was screened in a few theatres.

American producers began dubbing films on a larger scale during the Second World War, in the months leading up to the Liberation of France. In November 1943, the Capitol cinema in Quebec City, run at the time by Famous Players, presented Le ciel et toi, a dubbed version of Anatol Litvak’s 1940 film All This, and Heaven Too. It was immediately successful. In April 1944, Famous Players began programming dubbed films at Montreal’s Orpheum theatre. For a time, the Orpheum was the only cinema in Montreal to show dubbed American films. In Trois-Rivières, the Capitol presented its first dubbed film in August 1944: Blanche-neige et les sept nains (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs).

Other cinemas in the Odeon chain soon followed suit, to the delight of unilingual French speakers, who could finally understand what Bette Davis or John Wayne were saying. They had to wait a long time to see these versions, however. Right up until the 1950s, dubbed versions often showed up on movie screens more than two years after the original. The famous Gone with the Wind (1939), for example, only became Autant en emporte le vent in 1955. Because of this delay, film buffs took up the habit of going to see the original version when it was first released, to the great satisfaction of distributors.

French-language cinema, practically absent from Quebec in 1930, was shown in 10% of movie theatres by 1940. That’s not a lot, but at least it was found in every large and medium-sized city in the province. This success was due almost entirely to films from France. Not for another decade would this figure be doubled, to 20% of movie theatres showing only films in French.

French in a Variety of Accents

By the early 1950s, the success of “French talkies” was not due solely to events in the mother country, because Quebec films had achieved a very visible presence on the province’s movie screens. The success of Fedor Ozep’s Le père Chopin in 1945 inaugurated a period during which great numbers of people went to the movies to admire the stars made extremely popular by radio and theatre. Viewers were happy to hear their own language in these “big pictures”. In Le père Chopin, the Quebec accent of the actors Guy Mauffette, Pierre Dagenais and Ovila Légaré could be heard alongside the very Parisian accent of Marcel Chabrier, Madeleine Ozeray and François Rozet, to the delight of viewers, who were happy to hear the tonalities of their own environment while at the same time being at ease with the elocution of their French “cousins”.

The dozen films which followed Le père Chopin during this period demonstrated the interest of French Canadians in local films. They were the most profitable of all films distributed at the time, proof that French speakers adore the stories found on the big screen. Some were told with a regional accents (Paul Gury’s Un homme et son péché and Séraphin, René Delacroix’s Le gros Bill, Jean-Yves Bigras’ La petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre) while others seemed to want to promote “good French speaking” in the style of the campaigns by the nationalist elite (Fedor Ozep’s La forteresse, René Delacroix’s Le rossignol et les cloches, Jean-Yves Bigras’ Les lumières des ma ville). Gratien Gélinas, for his part, did not hesitate to Tit-Coq, in the film of the same name, speak in a pure, Montreal working-class accent.

National Pride as a Bonus

In the 1930s, Quebec political figures heralded the arrival of talkies from France, deeming that they would be a powerful tool for promoting good French and national pride. They hoped they would “serve as a good example and educate our ears at the same time as our minds” (Henri Letondal). With the arrival of French-Canadian cinema, an important step towards the accomplishment of these objectives was achieved.