Censorship

-

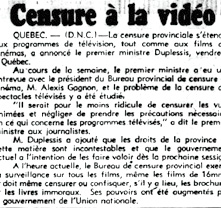

La Patrie, 10 February 1947, p.6

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

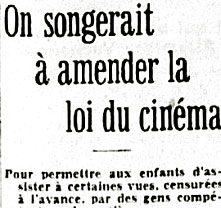

Le Petit Journal, 5 October 1952, p.34

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

L'Action Catholique, 6 February 1940, p.3

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

-

An image from the film Les enfants du paradis (Marcel Carné, 1945)

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1994.2687.PH.07

-

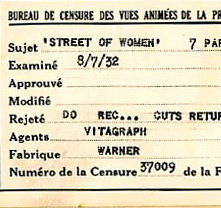

File card of the Board of Censors of Moving Picture of the Province of Quebec.

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise 2005.0147.01.AR.04

-

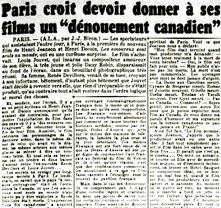

Le Petit journal, 3 October 1948, p.29

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

The first decades of talking cinema came at a time in Quebec history known as the Great Darkness. Film censorship played an important role during this period.

Not everything should be said

With talking films, not only images had to be censored, but also words. In the first place this posed a technical problem for the censors, who were unable to cut the records film soundtracks were often recorded onto in the early years of the talkies. Cuts to the images also became visible, because the censors were obliged to replace the section cut with black leader to maintain synchronisation with the soundtrack. The widespread use of optical sound beginning in the early 1930s solved these problems and simplified the censors’ task.

Many famous lines of dialogue were cut from prints of films shown in Quebec. The communist Cognasse (in Louis Mercanton’s film of the same name) could not be allowed to say “Neither God nor Master” or “property is theft”. Quebec audiences did not hear Mae West say “So many men, so little time” or “It’s easy to get married, but hard to stay that way”.

More children in commercial movie theatres

The Laurier Palace tragedy in 1927 led to an important change in censorship legislation a year later: children under 16 years of age were prohibited from commercial movie theatres at all times. This measure remained in place until 1961, when children were allowed entrance before 6:00 p.m. Exhibitors fought this regulation, and several flaunted it, but at the price of legal proceedings and fines. The only exception to the law was when cinemas showed films for children, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1938).

In the hearings preceding the 1928 law, religious figures also violently protested against advertisements for films, which they saw as often being immoral. The new law subjected them to censorship; movie posters and newspaper ads now had to be approved. This did not change until 1985.

A strict moral code

Another result of the tragedy and all the reaction against cinema it set in motion was the Bureau de censure’s adoption in 1931 of a very strict moral code which replicated almost in its entirety the Production Code governing American studios. Thousands of films were banned or mutilated. The percentage of films definitively banned generally never rose above 2%, but some 30% of films were cut. What was cut from them? Scenes whose eroticism or violence was deemed too explicit, but also anything that might offend the Catholic faith, such as John Adolfi’s film Voltaire or William Dieterle’s The Life of Emile Zola.

Because French films enjoyed greater freedom in their depiction of sexual relations and morality, they became the primary victim of Quebec’s censors. Marcel Carné’s films, including Hôtel du Nord and Le jour se lève, particularly suffered; Les enfants du paradis (The Children of Paradise) was banned completely, the very day of a gala screening at the Université de Montréal in February 1947, provoking a diplomatic incident with the French government. Even Marcel Pagnol’s comedies lost some of their repartee.

American films, which were already highly censored at the scriptwriting stage, were not spared. Films with a great deal of urban violence, such as Howard Hawks’s Scarface or Michael Curtiz’s Angels with Dirty Faces, were banned upon release and could only be seen much later, with cuts. Even newsreels were censored when they covered communist countries or fashion shows whose low-cut dresses and bathing suits revealed too much skin. The height of prudishness was reached when the censor cut the scene from Chaplin’s City Lights in which the tramp contemplates the statue of a nude woman in a shop window.

Can censorship be softened?

In the hope of softening the censorship of French films somewhat, in 1938 France-Film formed its own evaluation committee to guide the views of the government censors. The priest of the Cathédrale de Montréal, Adélard Harbour, the management of France-Film and occasional public figures screened the films distributed by the company. They gave them a rating and suggested what should be cut. Nevertheless, they did not succeed in softening the Bureau de censure, which was always stricter than they were.

Because censorship jobs had always been given to friends of the party in power in exchange for services rendered, their number more than doubled after the Second World War, from three to seven; by 1960 there were a dozen members. The Union nationale had a lot of friends to reward . . .

Censorship extends its tentacles

The parish and school network, with their 16mm projectors, also began to show increasing numbers of entertainment films that had been distributed commercially two or three years earlier. Paradoxically, these prints sometimes included scenes that had been cut from the official release of the film in 35mm.

In 1947, the Quebec premier, Maurice Duplessis, to whom the Bureau de censure reported, ordered it to censor all films distributed in 16mm, something that had never been done before. The principal target of this measure was films made by the NFB during the Second World War, which were accused of being communist propaganda.

At the same time, the law upheld the interdiction of drive-in movie theatres, venues greatly appreciated by young parents, who could watch the film while their infant slept in the back seat, and especially by teenagers, for their own reasons, giving drive-ins the reputation of being “sin pits”.

As the period drew to a close, film censorship was more severe than it had even been. The Bureau de censure was run with an iron fist by Alexis Gagnon. It wasn’t until the early 1960s that the situation began to change.