Hollywood in Quebec

-

Montgomery Clift and Anne Baxter in front of the Château Frontenac during the production of the film I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock, 1953).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1994.4203.PH

-

Image from the film The 13th Letter (Otto Preminger, 1951).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.0279.PH.01

-

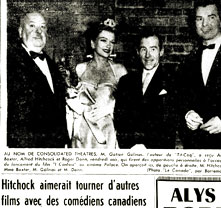

Le Canada, 16 February 1953, p.18

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

Poster for the film I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock, 1953).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1988.2580.AF

-

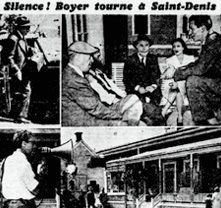

Le Petit journal, 24 September 1950, p.73

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1988.2299.AF

When the little guy makes the big guy rich

In the years following the Second World War, Canada saw its trade deficit with the United States grow. For example, many more Canadians took their vacations in Florida or on the beaches of Maine than Americans visited the Gaspé region. In the film industry alone, Hollywood studios earned 17 million dollars in Canada, a considerable sum, while no Canadian feature film was exhibited in the United States.

To counter this imbalance, the federal government introduced a bill that would prohibit the exodus of some of this capital, forcing the major studios to spend the money in Canada and—why not?—to invest in local cinema. Some people even pictured limiting the presence of American films on Canadian movie screens in order to give Canadian films a better chance, as several developed countries do.

An agreement that might pay off

The American response was not long in coming. The majors would not hear of a law restricting free trade. Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, travelled to Ottawa to lobby the government with the help of J.J. Fitzgibbons, president of Famous Players Canadian Corporation, and to propose “voluntary” measures to promote the Canadian film industry. After several months of discussions, the majors and the government of Canada announced in 24 January 1948 the establishment of the Canadian Co-operation Project, which remained in effect for ten years.

The agreement had five principal objectives:

1. To obtain more American location shooting in Canada;

2. To sell more Canadian films into the U.S. market;

3. To give Canadian capital an opportunity to invest in American films;

4. To promote American tourism in Canada;

5. To present general information about Canada in films distributed in the United States.

What were the results?

Hollywood in Quebec?

A few film shoots did in fact take place in Canada.

In Quebec, Otto Preminger came to Saint-Hilaire and the studios of Québec Productions in 1951 to shoot The 13th Letter, a remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le corbeau (The Raven), but without the original’s subversive elements. In fact the events depicted as taking place in the small provincial town of “Saint Marc sur le Richelieu” had nothing in common with what happened in the small French town of Saint-Robin. In the end, it was a banal film that was released in Quebec in its original English-language version only and was treated by French-speaking critics as if it didn’t exist.

Alfred Hitchcock was next, coming in 1952 to film I Confess, a film that did no injustice to the great filmmaker’s reputation. Hitchcock skilfully recreated the atmosphere of Quebec City’s narrow streets and made intelligent use of the Catholic religion’s code of secrecy around what is said in the confessional to create his brand of suspense, in which only the viewer knows who the murderer is. In 1995, Robert Lepage’s film Le confessional masterfully evoked everything surrounding the production of Hitchcock’s film and its influence on Quebec City.

In the end, a market of suckers

The only other effect of the agreement was a few laughable references to Canadian ‘reality” such as “mountaineers from Winnipeg” or splendid forests in which bandits on the run find safe hiding places. Mocking these references, John Kramer entitled his film about Canadian film history from 1939 to 1953 Has Anybody Here Seen Canada?, one of the vague allusions to Canada found in minor films. As for the distribution of Canadian films in the United States, for all intents and purposes there was none, except perhaps a few National Film Board shorts given for free to Columbia.