Cinema and Religion

-

Le Canada, 3 July 1936, p.1

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

Le Petit Journal, 17 February 1935, p.17

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

L'Action catholique, 23 April 1945, p.14

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

L'Action catholique, 20 November 1937, p.23

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

Rural folk praying in Hommage à notre paysannerie (Albert Tessier, 1938).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.6023.PH.02

-

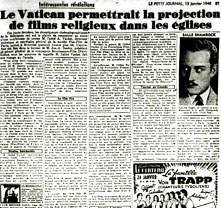

Le Petit Journal, 13 January 1946, p.37

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

Reciting the rosary in Cantique du soleil (Albert Tessier, 1935).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.0686.PH.01

During the silent period, Quebec’s Catholic Church was opposed to cinema, calling it “the devil’s night classes”. It tirelessly demanded that children be spared this “scourge”. After the Laurier Palace tragedy in 1927, the Church finally succeeded in persuading the provincial government to pass a law banning children under 16 from commercial movie theatres. In 1928 it also obtained tougher new censorship laws. Its directives inspired the rewriting of the code used by the censors.

Nevertheless, many Quebec educators recognised cinema’s value as a pedagogical tool. Many clerics and nuns began to offer film screenings in schools, parish halls, etc. They also wanted to provide children with “healthy distractions”. Films by amateur filmmaker priests—informative short films on a variety of topics—were shown there. Soon, however, they had access to 16mm prints of films that had previously been shown in commercial movie theatres.

Inform people about film’s moral virtues

In 1936, the encyclical Vigilanti Cura decreed that the cinema is not harmful in itself but rather a tool that can be used for good as well as evil. How could one tell good films from bad? The pope recommended that dioceses set up evaluation committees which would then make their views known. The Catholic Church’s standard bearers, the newspapers Le Devoir in Montreal and L’Action catholique in Quebec City, began publishing these moral ratings in 1937. The system was refined in January 1948 when the Montreal diocese’s Action catholique began distributing a weekly bulletin, Ciné-service, inaugurating its famous ratings: “For all”, “Adults and teenagers”, “Adults”, “Adults with reserve”, “Not recommended” and “To be avoided”, which remained in effect for twenty years and were adopted by every diocese in the province.

“If you can’t beat them . . .”

If you can’t beat them, join them, the old saying goes. The pope also encouraged the faithful to establish a Catholic film production industry. This was received as a considerable encouragement by amateur religious filmmakers. Even nuns began making “prayer films” in the hope of attracting new recruits. Under the aegis of Jeunesse étudiante catholique, the Catholic youth league, screenings in colleges and universities soon gave rise to the establishment of film societies, places of discussion that served as hothouses for film buffs and many filmmakers.

After the Second World War, promoters of fiction films in commercial movie theatres sought the support of the clergy. J.A. DeSève developed a large program of films of “Catholic inspiration” of interest to audiences of all kinds. His partner in Renaissance Films Distribution, the priest Aloysius Vachet, brought with him the experience he acquired in his studio in France, Fiat Films. Vachet became a propagandist of the “good news” in Le Devoir, at Radio-Canada and even in Sunday masses given in dozens of parishes.

In the early 1950s, clerical influence rapidly declined and the Church’s all-powerful status came to an end.