French Canadians at the NFB

-

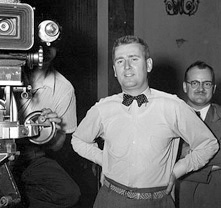

Roger Blais on the set.

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 2007.0071.PH.02

-

An image from the film L’homme aux oiseaux (Bernard Devlin and Jean Palardy, 1952).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise 1999.0008.PH

-

Photographic portrait of Raymond Garceau.

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 2000.0054.PH.02

When John Grierson took up his duties as the founder of the National Film Board of Canada in 1939, he believed that it was pointless to devote significant resources to the production of films for French Canadians alone. As a result, no French-speaking filmmakers were hired. In December 1941 the distribution head of the organisation and its sole francophone, Philéas Côté, impressed upon Grierson the need to supply French-Canadian audiences with films which matched their specific features. The NFB then hired its first French-Canadian filmmaker, Vincent Paquette, and put him in charge of its Montreal office. In 1942, Paquette recruited several collaborators, such as Jean Palardy and Jean-Yves Bigras, took up the preparation of French versions of NFB films and developed a French-language production program, the series “Les Reportages”. The hiring of French-speaking personnel throughout 1943 soon achieved a certain critical mass: some fifteen people (around one-sixth of the NFB’s staff) and a French-language studio. The “Les Reportages” series enabled them to deal specifically with life in Quebec in wartime. In 1944, the NFB even recruited someone to advise the commissioner on French-Canadian issues, supervise the production and distribution of French-language films and hire the necessary personnel. Within a year, the roster of film directors was augmented by six new people, including Roger Blais, Raymond Garceau, Pierre Petel and Bernard Devlin. Nevertheless, only one studio out of twelve had a mandate to produce films in French, and of the NFB’s 147 production personnel, only 25 were francophone.

During the war, French-speaking directors made a hundred or so films, enabling them to make visible for the first time their society and its people. Nevertheless, under the pretext of having inexperienced filmmakers (read: French speakers) work with experienced directors and not confine them to a milieu in which they could not develop, in late 1994 and early 1945 the NFB decided to mix French speakers with English speakers in the same studio. French-Canadian filmmakers were thus prevented from making films in their own language. The French language’s only place was in French versions of English films. In every other respect, the situation deteriorated. Many French Canadians, less well paid than their English-speaking colleagues, without encouragement and limited in their production opportunities, left the NFB. In 1948 a re-organisation brought about the dissolution of the French studio. French Canadians were now dispersed throughout the structure, and management was convinced it was meeting French-speakers’ needs by increasing the amount of dubbing done. As a result, it did not encourage original production in French, which practically disappeared.

In 1950, the NFB’s board of directors estimated that, in order to maintain high-quality production, the organisation should be located in a city with an intense cultural life. It recommended Montreal. Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent supported the idea. At the same time, a number of demands with respect to the number of French-language films produced were brought before the Massey Commission. NFB management, however, believed their cost to be disproportionate to the limited population. The cost argument seemed to take precedence over that of cultural rights.

In 1952, in fact, it was observed that French-speaking filmmakers were being assimilated, something reinforced by their structural immersion. This did not mean, however, that they were resigned to the situation, or that they and figures outside the NFB did not push it to change. To meet the needs of television, in 1953 Roger Blais took over a studio delegated to make films in French. In order to counter the opposition of senior English-speaking management personnel, the board of directors decided in 1954 to create the post “French Adviser”, which was fused with that of secretary to the board. The first person to occupy this position, Pierre Juneau, encouraged the production of more films in French.

In 1955 an intensive media campaign was launched to denounce the situation of French Canadians at the NFB. Three measures came out of this initiative: a second studio was created to handle French versions; an executive producer was recruited for the French-language program; and foreign filmmakers, such as Georges Dufaux, were hired to reinforce French-speaking personnel. The effects of these measures were felt after the NFB moved to Montreal in 1956. In fact as long as the NFB was in Ottawa, French Canadians had limited awareness of their identity and specificity. This did not prevent them from expressing in their work, on occasion, content that addressed the culture, ways of thinking and values of French-Canadian society. In Montreal, they were regrouped into teams to meet the need to produce a certain number of films in French. At the same time, the move enabled them to work together, to build a degree of cohesion amongst themselves and, increasingly, to express their demands. They had learned to use the relative autonomy within this state body which they acquired after 1956.