Settling the Land

-

Land before being cleared. An image from the film En pays neufs : Sainte-Anne-de-Roquemaure (Maurice Proulx, 1942).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.1091.PH.04

-

Settlers working the land using traditional techniques in the film Abitibi (1949).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.0356.PH.05

-

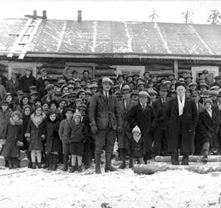

An image from the film En pays neufs : Sainte-Anne-de-Roquemaure (Maurice Proulx, 1942).

Source : Cinémathèque québécoise, 1995.1091.PH.02

Surviving the economic crisis

The world economy went into crisis in 1929 and did not spare Quebec, leading the government to launch a new phase of settling the land. In the late nineteenth century, the opening up of considerable areas of the Laurentians, north of Montreal, had provided an outlet for many unemployed young men in the city.

In the 1930s, Quebec premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau provided numerous settlement organisations the means to go work the land in a number of regions, from Abitibi to Lac Saint-Jean and from Témiscouata to the Gaspé. Everywhere large sections of forest gave way to cultivated land. Soon villages and then towns were providing settlers with health-care and education facilities. Greater and greater areas of Quebec were becoming occupied.

Filming the settlers for the first time

This time, the settlement projects were filmed—an extraordinary novelty. In 1934 the agronomist and priest Maurice Proulx accompanied a group of settlers to Roquemaure in the Abitibi region of the province. He recorded their principal everyday activities and their way of organising communal life. We see them using bygone tools (the adze, the mitre-box saw, the two-man saw) to build houses out of squared timber and then to clear the land and plough it with teams of oxen. Proulx’s images were silent, but he commented on them in dozens of lectures. His clearly propagandistic goal was to promote participation in the founding of new areas of Quebec. In his films, everything was fine, the settlers wore big smiles, and no one had any special problems. The reality, as we would discover later in Bernard Devlin’s fiction film Les brûlés, was not so idyllic.Proulx returned to each location for three more consecutive years, taking new footage each time.

A 1934 short film thus soon became a feature, En pays neufs. Beginning with the second year’s shooting, he structured his footage around the paradigm of progress: the first log chapel becomes a handsome plank church; the “garde Bédard” (nurse) travelled at first on foot, then on horseback, and finally by automobile; after vegetables, the settlers could now plant flowers; newspapers (L’Action catholique) now reached the village community; etc. In 1937, the Ministère de Colonisation decided to use the film as a propaganda tool, providing money for a sound version and for additional prints to be struck. Proulx returned to Abitibi in 1942 to shoot a colour epilogue to En pays neufs, entitled Sainte-Anne-de-Roquemaure, in which he showed the settlers’ latest progress in a most favourable light.

Proulx then filmed settlement efforts or their results in various regions, especially in the Gaspé (En pays pittoresque) in a village called Saint-Octave-de-l’Avenir. There, ironically, Marcel Carrière would shoot heart-rending images of the town being closed up in 1971 and 1972.Emblematic images of the early years of Quebec. Proulx’s films not only reveal the 1930s to us; they symbolise the founding of the nation in its very early years. For the gestures recorded by Proulx greatly resemble those of the first to discover and cultivate the land. In the four years during which Proulx filmed a region we witness in fast-motion nearly three hundred years of history.In the early 1950s, the fictional saga Un homme et son péché, followed by Séraphin, returned to the settlement era of the late nineteenth century. In these films also, but this time in fiction, the settlers’ spirit and their reactions to the difficulties they encountered were expressed.